As the war in Gaza grinds on, Israel's international isolation appears to be deepening.

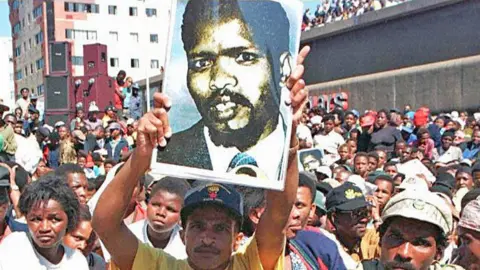

Is it approaching a South Africa moment, when a combination of political pressure, economic, sporting and cultural boycotts helped to force Pretoria to abandon apartheid?

Or can the right-wing government of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu weather the diplomatic storm, leaving Israel free to pursue its goals in Gaza and the occupied West Bank without causing permanent damage to its international standing?

Two former prime ministers, Ehud Barak and Ehud Olmert, have already accused Netanyahu of turning Israel into an international pariah.

Thanks to a warrant issued by the International Criminal Court, the number of countries Netanyahu can travel to without the risk of being arrested has shrunk dramatically.

At the UN, several countries, including Britain, France, Australia, Belgium and Canada, have said they are planning to recognise Palestine as a state next week.

And Gulf countries, reacting with fury to last Tuesday's Israeli attack on Hamas leaders in Qatar, have been meeting in Doha to discuss a unified response, with some calling on countries which enjoy relations with Israel to think again.

But with images of starvation emerging from Gaza over the summer and the Israeli army poised to invade - and quite possibly destroy - Gaza City, more and more European governments are showing their displeasure in ways that go beyond mere statements.

At the start of the month, Belgium announced a series of sanctions, including a ban on imports from illegal Jewish settlements in the West Bank, a review of procurement policies with Israeli companies and restrictions on consular assistance to Belgians living in settlements.

Other countries, including Britain and France, had already taken similar steps. But sanctions on violent settlers imposed by the Biden administration last year were scrapped on Donald Trump's first day back in the White House.

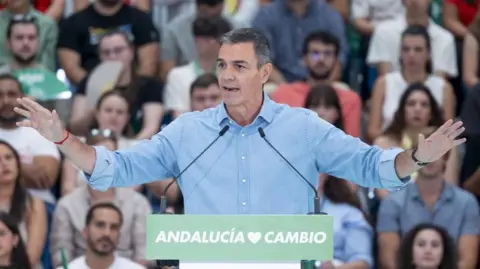

A week after Belgium's move, Spain announced its own measures, turning an existing de facto arms embargo into law and prohibiting Israel-bound ships and aircraft carrying weapons from docking at Spanish ports or entering its airspace.

In August, Norway's vast $2tn sovereign wealth fund announced it would start divesting from companies listed in Israel, while the EU plans to sanction far-right ministers and partly suspend trade elements of its association agreement with Israel.

One feature of the sanctions levelled at South Africa during the 1990s was a series of cultural and sporting boycotts, a trend some are now seeing in Israel, with countries hinting at withdrawal from events like the Eurovision Song Contest unless Israel is allowed to participate.

Additionally, a letter circulating in Hollywood calls for a boycott of Israeli production companies, echoing earlier sentiments in the music and sports communities about Israel’s actions.

While Netanyahu remains defiant, claiming that such actions are rooted in anti-Semitism, former diplomats caution against these broad sanctions that could alienate moderate Israelis and prompt a shift towards hard-liners.

As the international landscape changes, observers remain divided on whether Israel is truly on the brink of a significant diplomatic transformation or if it can maintain its current stance amidst growing isolation.