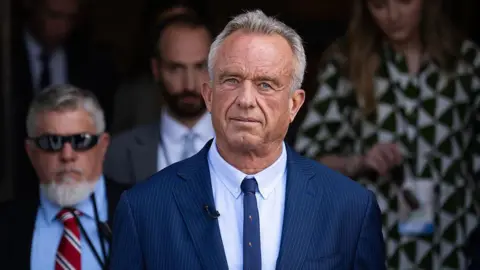

In fiery Senate testimony this week, US Health Secretary Robert Kennedy Jr once again set his sights on the nation's top public health agency, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

His appearance came days after he suddenly fired the new CDC director, Susan Monarez, provoking a group of senior staff to resign in protest.

At the hearing, when asked for an explanation, Kennedy claimed he had asked Ms Monarez if she was a trustworthy person and she had replied no, to some disbelief from his opponents in the room.

He then admitted he had once described the CDC as the most corrupt agency in government, and strongly hinted he's not finished with his plans to shake up the organisation.

Kennedy's words have sparked a furious backlash, with many doctors and scientists increasingly concerned that America's public health systems are being dangerously compromised.

It's a conflict that could have a significant impact not just on health policy in the US but across the world. In the past, the CDC has been instrumental in global health, leading the response to crises from famine, to HIV, to Ebola.

Founded in 1946, the CDC tracks emerging infectious diseases like Covid and is also tasked with tackling long-term or chronic conditions such as heart disease and cancer.

It operates more than 200 specialised laboratories and employs 13,000 people, although that number has been cut by around 2,000 since President Donald Trump returned to office. It does not approve or licence vaccines. That responsibility lies with the Food and Drug Administration.

But it does produce official recommendations on who should receive which vaccines through a panel of experts - known as the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) - and monitors their side effects and other safety concerns.

It was Kennedy's record on vaccines which particularly worried many public health experts when he took office in February.

An activist group he ran for eight years, Children's Health Defense, repeatedly questioned the safety and efficacy of vaccination.

He has described the Covid jab as the most deadly in history and has blamed rising rates of autism on vaccines, an idea that has been categorically debunked by large scientific studies over many years.

So feathers were seriously ruffled just weeks into his tenure when it emerged he had hired a noted vaccine critic, David Geier, to look again at the CDC data on that scientifically disproven link.

Then in June, Kennedy suddenly sacked the entire ACIP panel which advises the CDC on vaccine eligibility after accusing all 17 members of being plagued with persistent conflicts of interest.

A new committee, handpicked by the administration, now has the power to change, or even drop, critical recommendations to immunise Americans for certain diseases, as well as shape the childhood vaccination programme, although the CDC itself still has the final say on whether to accept that advice.

In his testimony Kennedy stood his ground, accusing her of lying about that exchange and describing her dismissal as absolutely necessary. He asserted a need for new leadership at CDC to foster a new course in public health.

His tumultuous leadership, including the recent sacking of Monarez, has heightened scrutiny over CDC's future as a crucial authority in global health initiatives, raising alarms over potential impacts during the next public health emergency.

As the CDC prepares for its upcoming advisory panel meeting on September 18, global observers anxiously wait to see how Kennedy's decisions will shape vaccine policies and public health trust both domestically and internationally, amid concerns of politicization of health information.