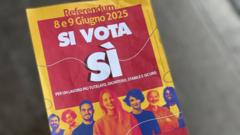

The proposed referendum seeks to reduce the application timeline for Italian citizenship from ten to five years, but faces significant political opposition. Activists argue for the rights of long-term residents while government leaders encourage voter apathy.

Italian Citizenship Referendum Sparks Controversy and Deepens Divisions in Society

Italian Citizenship Referendum Sparks Controversy and Deepens Divisions in Society

A national referendum aiming to reform Italy's citizenship rules has ignited debates and underscored the ongoing struggles of long-term residents.

Italian citizenship is at the forefront of a polarizing national debate as a referendum approaches this Sunday and Monday. The proposed measure aims to reduce the waiting period for long-term residents seeking citizenship from ten years to five, aligning Italy's policies more closely with those of other European nations. Among those championing the cause is Sonny Olumati, a 39-year-old activist born and raised in Italy but still lacking citizenship.

“I've been born here. I will live here. I will die here,” Sonny states, explaining how not having citizenship feels like a denial of belonging. His sentiments resonate with many who share his plight, prompting a campaign advocating for a "Yes" vote.

However, the push for change faces a significant hurdle in the form of Italy’s hard-right Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, who announced her intention to boycott the vote, claiming that the current citizenship laws are adequate. Her coalition partners have encouraged Italians to skip the polls and spend their time at the beach instead, undermining the referendum's significance.

This contentious issue is set against a backdrop of increasing migrant arrivals in Italy, a situation that the Meloni administration has made a priority to control. Nevertheless, the proposed reforms are specifically tailored for those who have legally worked in the country, unlike the broader immigration narrative often discussed in political circles.

Supporters of the referendum, including Carla Taibi of the liberal party More Europe, emphasize that this change is limited in scope and doesn’t alter stringent criteria such as demonstrating language proficiency or having a clean criminal record. The reforms could benefit up to 1.4 million residents, facilitating their integration into society while also allowing their children under 18 to become Italian citizens.

Despite the potential for progress, the referendum has received minimal coverage from state-run media, with critics alleging that the government aims to suppress turnout to ensure the referendum fails. Professor Roberto D'Alimonte from Luis University highlights a strategic motive behind the political silence, suggesting that the government believes low awareness can help prevent the turnout threshold necessary for validity—over 50% participation.

Olumati’s case sheds light on the often painful and frustrating journey of those in limbo. He attributes his prolonged wait for citizenship to underlying racism and institutional inefficiencies. Insaf Dimassi, another advocate, shares similar feelings of being "Italian without citizenship," recounting her struggles with identity and belonging in a country she has always called home.

As the referendum looms, many advocates are hoping that a visible turnout can overturn the planned boycott. Students in Rome have taken the initiative to create awareness by writing encouragements to vote in public squares. Yet, the likelihood of achieving the necessary turnout remains uncertain given the governmental stance.

Despite these challenges, Olumati remains hopeful: "Even if they vote 'No', we will stay here – and think about the next step," he asserts, indicating that this movement is just the beginning of a larger conversation about belonging in Italy.