Warning: This article contains disturbing details from the start.

A group of children spotted Adel's body on their way to school, just as his parents were heading to the police station to report him missing. A grotesque, charred silhouette, reclining, with one knee raised, as if lounging on one of Marseille's nearby beaches.

He was 15 when he died, in the usual way: a bullet in the head, then petrol poured over his slim corpse and set on fire.

Someone even filmed the scene on the beach, the latest in a grim series of shoot-then-burn murders linked to this port city's fast-evolving drug wars, increasingly fueled by social media and now marked by chillingly random acts of violence and by the growing role of children, often coerced into the trade.

It's chaos now, said a scrawny gang member, lifting his shirt in a nearby park to show us a torso marked by the scars of at least four bullets - the result of an attempted assassination by a rival gang.

France's Ministry of Justice estimates that the number of teenagers involved in the drugs trade has risen more than four-fold in the past eight years.

I've been in [a gang] since I was 15. But everything has changed now. The codes, the rules – there are no more rules. Nobody respects anything these days. The bosses start... to use youngsters. They pay them peanuts. And they end up killing others for no real reason. It's anarchy, all over town, said the man, now in his early 20s, who asked us to use his nickname, The Immortal.

Across Marseille, police, lawyers, politicians, and community organizers talk of a psychose – a state of collective trauma or panic – gripping parts of the city, as they debate whether to fight back with ever tougher police action or with fresh attempts to address entrenched poverty.

It's an atmosphere of fear. It's obvious that the drug traffickers are dominant, and gaining more ground every day, said a local lawyer, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals against her or her family.

The rule of law is now subordinate to the gangs. Until we have a strong state again, we have to take precautions, she said, explaining her recent decision to stop representing victims of gang violence.

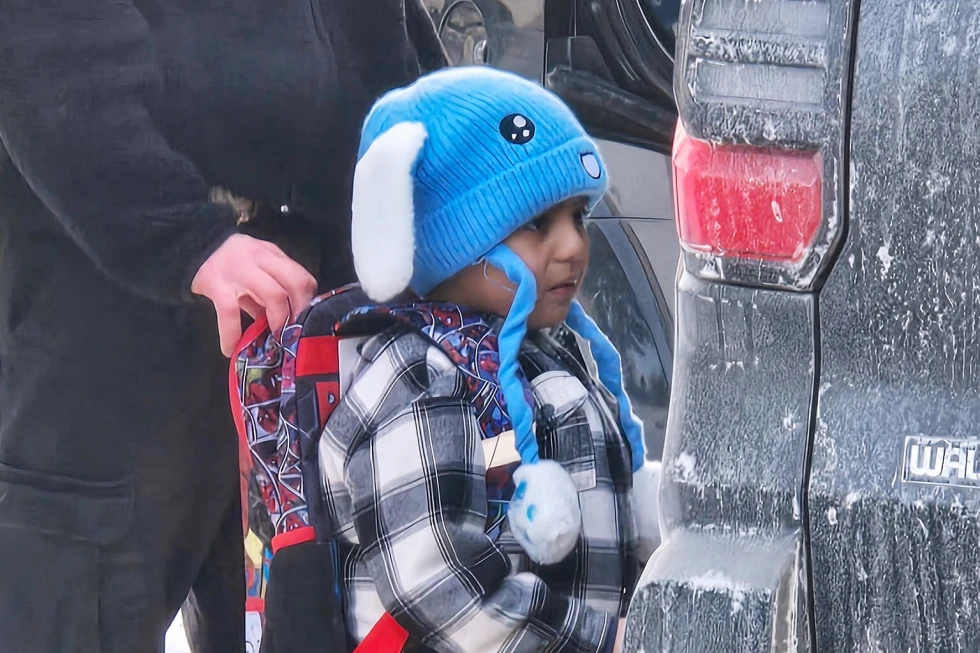

There's so much competition in the drugs trade that... people are ready to do anything. So, we have kids aged 13 or 14 who come in as lookouts or dealers. The young see dead bodies, they hear about it, every day. And they're no longer afraid of killing, or being killed, community organizer Mohamed Benmeddour told us.

The trigger for Marseille's current psychose was the murder, last month, of Mehdi Kessaci, a 20-year-old trainee policeman with no links to the drug trade. It is widely believed his death was intended as a warning to his brother, a prominent 22-year-old anti-gang activist and aspiring politician named Ahmed Kessaci.

Under close police protection now, Kessaci spoke to the BBC about Mehdi's death, and the guilt he feels.

Should I have made my family leave [Marseille]? The struggle of my life is going to be this fight against guilt, he said.

Ahmed Kessaci first rose to national prominence in 2020, after his older brother, a gang member named Brahim, was also murdered.

We've had this psychose for years. We've known that our lives are hanging by a single thread. But everything changed since Covid. The perpetrators are getting younger and younger. The victims are younger and younger, he said.

My little brother was an innocent victim. There was a time when the real thugs... had a moral code. You don't kill in daytime. Not in front of everyone. You don't burn bodies. First you threaten with a shot to the leg... Today these steps have all disappeared.

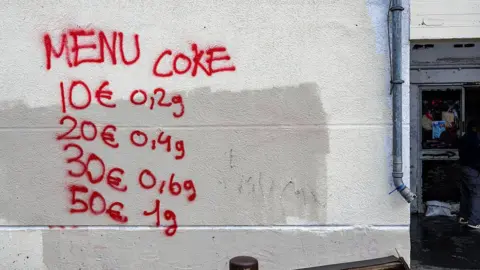

French police are responding with security bombardments in high-crime areas of Marseille. Notably, one gang, the DZ Mafia, now appears to dominate the trade, but operates through a network of small distributors often staffed by teenagers and undocumented immigrants.

Local prosecutors have called for community action against this disturbing trend, rallying residents not to give in to fear, and to combat the conditions that blindly perpetuate this cycle of violence.

A group of children spotted Adel's body on their way to school, just as his parents were heading to the police station to report him missing. A grotesque, charred silhouette, reclining, with one knee raised, as if lounging on one of Marseille's nearby beaches.

He was 15 when he died, in the usual way: a bullet in the head, then petrol poured over his slim corpse and set on fire.

Someone even filmed the scene on the beach, the latest in a grim series of shoot-then-burn murders linked to this port city's fast-evolving drug wars, increasingly fueled by social media and now marked by chillingly random acts of violence and by the growing role of children, often coerced into the trade.

It's chaos now, said a scrawny gang member, lifting his shirt in a nearby park to show us a torso marked by the scars of at least four bullets - the result of an attempted assassination by a rival gang.

France's Ministry of Justice estimates that the number of teenagers involved in the drugs trade has risen more than four-fold in the past eight years.

I've been in [a gang] since I was 15. But everything has changed now. The codes, the rules – there are no more rules. Nobody respects anything these days. The bosses start... to use youngsters. They pay them peanuts. And they end up killing others for no real reason. It's anarchy, all over town, said the man, now in his early 20s, who asked us to use his nickname, The Immortal.

Across Marseille, police, lawyers, politicians, and community organizers talk of a psychose – a state of collective trauma or panic – gripping parts of the city, as they debate whether to fight back with ever tougher police action or with fresh attempts to address entrenched poverty.

It's an atmosphere of fear. It's obvious that the drug traffickers are dominant, and gaining more ground every day, said a local lawyer, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals against her or her family.

The rule of law is now subordinate to the gangs. Until we have a strong state again, we have to take precautions, she said, explaining her recent decision to stop representing victims of gang violence.

There's so much competition in the drugs trade that... people are ready to do anything. So, we have kids aged 13 or 14 who come in as lookouts or dealers. The young see dead bodies, they hear about it, every day. And they're no longer afraid of killing, or being killed, community organizer Mohamed Benmeddour told us.

The trigger for Marseille's current psychose was the murder, last month, of Mehdi Kessaci, a 20-year-old trainee policeman with no links to the drug trade. It is widely believed his death was intended as a warning to his brother, a prominent 22-year-old anti-gang activist and aspiring politician named Ahmed Kessaci.

Under close police protection now, Kessaci spoke to the BBC about Mehdi's death, and the guilt he feels.

Should I have made my family leave [Marseille]? The struggle of my life is going to be this fight against guilt, he said.

Ahmed Kessaci first rose to national prominence in 2020, after his older brother, a gang member named Brahim, was also murdered.

We've had this psychose for years. We've known that our lives are hanging by a single thread. But everything changed since Covid. The perpetrators are getting younger and younger. The victims are younger and younger, he said.

My little brother was an innocent victim. There was a time when the real thugs... had a moral code. You don't kill in daytime. Not in front of everyone. You don't burn bodies. First you threaten with a shot to the leg... Today these steps have all disappeared.

French police are responding with security bombardments in high-crime areas of Marseille. Notably, one gang, the DZ Mafia, now appears to dominate the trade, but operates through a network of small distributors often staffed by teenagers and undocumented immigrants.

Local prosecutors have called for community action against this disturbing trend, rallying residents not to give in to fear, and to combat the conditions that blindly perpetuate this cycle of violence.