When insurgents finally gained control of the town of Kyaukme - on the main trade route from the Chinese border to the rest of Myanmar - it was after several months of hard fighting last year.

Kyaukme straddles Asian Highway 14, more famous as the Burma Road during World War Two, and its capture by the Ta'ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) was seen by many as a pivotal victory for the opposition. It suggested that the morale of the military junta which had seized power in 2021 might be crumbling.

This month, though, it took just three weeks for the army to recapture Kyaukme.

The fluctuating fate of this little hill town is a stark illustration of how far the military balance in Myanmar has now shifted, in favour of the junta.

Kyakme has paid a heavy price. Large parts of the town have been flattened by daily air strikes carried out by the military while it was in the hands of the TNLA. Air force jets dropped 500-pound bombs, while artillery and drones hit insurgent positions outside the town. Much of the population fled the town, though they are starting to return now the military has retaken it.

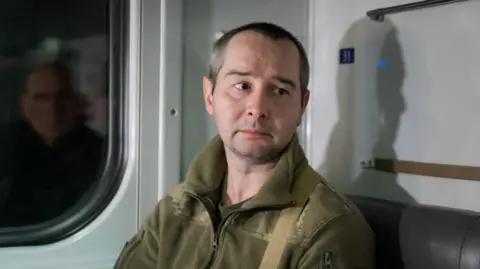

There is heavy fighting going on every day, in Kyaukme and Hsipaw, Tar Parn La, a spokesman for the TNLA, told the BBC earlier this month. This year the military has more soldiers, more heavy weapons, and more air power. We are trying our best to defend Hsipaw.

Since the BBC spoke to him the junta's forces have also retaken Hsipaw, the last of the towns captured by the TNLA last year, restoring its control over the road to the Chinese border.

These towns fell primarily because China has thrown its weight behind the junta, backing its plan to hold an election in December. This plan has been widely condemned because it excludes Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy, which won the last election but its government was ousted in the coup, and because so much of Myanmar is in a state of civil war.

That is why the military is currently trying to take back as much lost territory as it can, to ensure the election can take place in these areas. And it is enjoying more success this year because it has learned from its past failures, and acquired new and deadly technology.

In particular, it has responded to the early advantage enjoyed by the opposition in the use of inexpensive drones, by buying thousands of its own drones from China, and training its forward units how to use them, to deadly effect.

It is also using slow and easy-to-fly motorised paragliders, which can loiter over lightly-defended areas and drop bombs with high accuracy. And it has been bombing relentlessly with its Chinese and Russian supplied aircraft, causing much higher numbers of civilian casualties this year. At least a thousand are believed to have been killed this year, but the total is probably higher.

On the other side, the fragmented opposition movement has been hampered by inherent weaknesses.

It comprises hundreds of often poorly-armed people's defense forces or PDFs, formed by local villagers or by young activists who fled from the cities, but also seasoned fighters from the ethnic insurgent groups who have been waging war against the central government for decades. They have their own agendas, harbouring a deep mistrust of the ethnic Burmese majority, and they do not recognise the authority of the National Unity Government which was formed from the administration ousted by the 2021 coup. So there is no central leadership of the movement.

And now, more than four years into a civil war that has killed thousands and displaced millions, the tide is turning once again.

When an alliance of three ethnic armies in Shan State launched their campaign against the military in October 2023 - calling it Operation 1027 - armed resistance to the coup had been going on in much of the country for more than two years, but making little progress.

That changed with Operation 1027. The three groups, calling themselves the Brotherhood Alliance - the Ta'ang National Liberation Army, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army and the Arakan Army - had prepared their attack for months, deploying large numbers of drones and heavy artillery.

They caught military bases off-guard, and within a few weeks had overrun around 180 of them, taking control of a large swathe of northern Shan State, and forcing thousands of soldiers to surrender.

These stunning victories were greeted by the broader opposition movement as a call to arms, and PDFs began attacks in their own areas, taking advantage of low military morale.

As the Brotherhood Alliance moved down Asian Highway 14, towards Myanmar's second-largest city of Mandalay, there was open speculation that the military regime might collapse.

That did not happen.

However, there are many parts of Myanmar where the junta has been less successful. Armed resistance groups control most of Rakhine and Chin States, and are holding the military at bay, and even driving it back in places.

One factor in the military's recent victories is that it is concentrating its forces only in strategically important areas, Morgan Michaels believes, like the main trade routes, and towns where it would like to hold the election.

Meanwhile, tighter border controls and China's ban on the export of dual-use products are making it harder for the resistance groups to get access to drones, or even the components to assemble their own drones. Prices have risen steeply. And the military has much better jamming technology now, so many of their drones are being intercepted.

In summary, while Myanmar's junta has faced significant setbacks, China's increased support and technological advancements have allowed it to regain lost territory and reassert control over essential regions, complicating the ongoing civil war and humanitarian crisis.