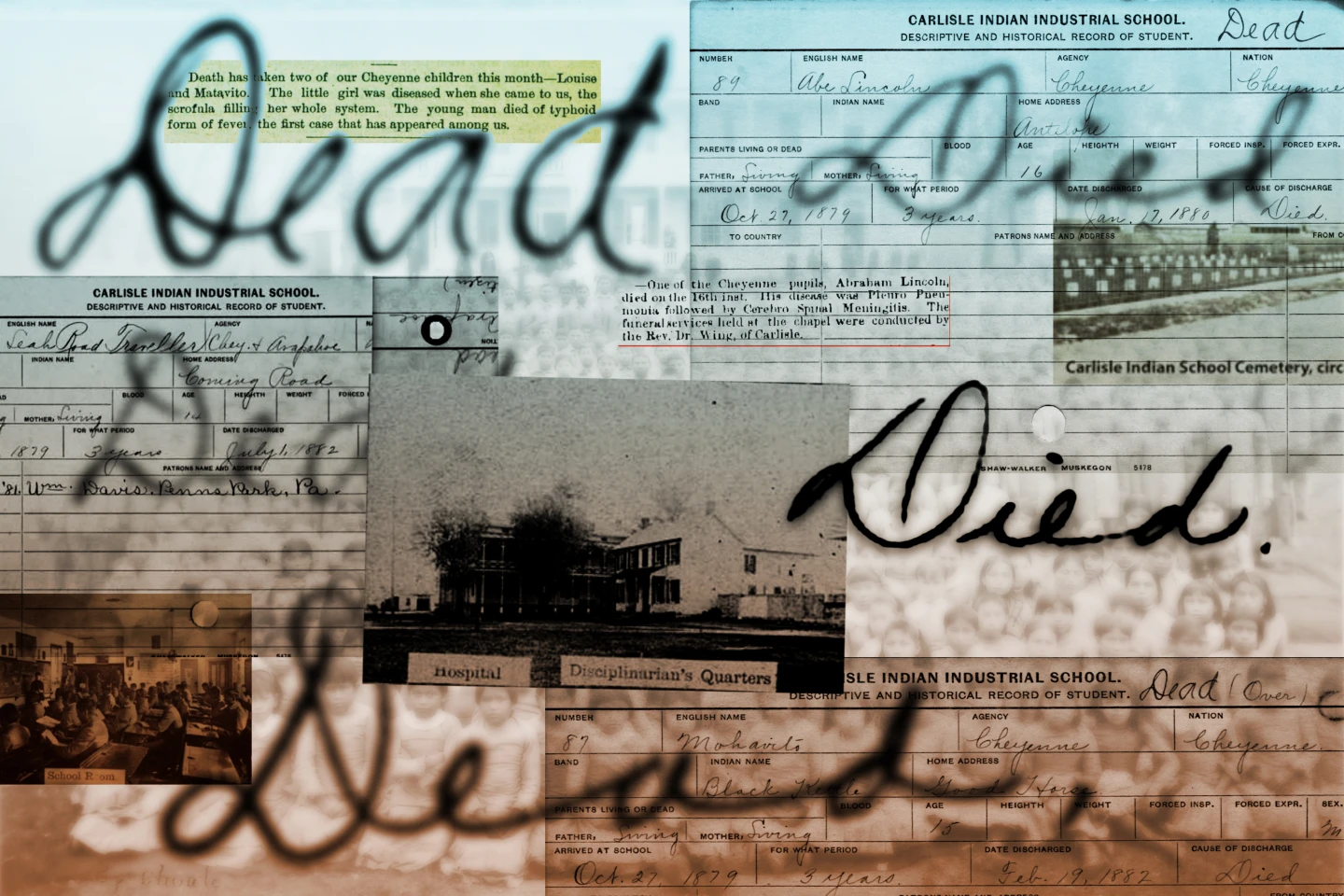

CARLISLE, Pa. (AP) — In October 1879, Matavito Horse and Leah Road Traveler were taken to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, an institution aimed at erasing Native American identities. Their tragic deaths followed, but persistent efforts from their tribes have finally reclaimed their remains, as the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes along with the Seminole Nation brought home 17 students exhumed from a cemetery.

Just last month, the Cheyenne and Arapaho buried their children’s wooden coffins in Concho, Oklahoma, while the Seminole Nation repatriated Wallace Perryman. According to tribal officials, these burial ceremonies symbolize a vital step towards justice and healing for families impacted by the historical era of boarding schools.

The plight of the 17 students at Carlisle, where over 7,800 children from more than 100 tribes were subjected to cultural assimilation, remains under examination. Many endured laborious tasks and harsh conditions at the institution. Some even fell victim to diseases like tuberculosis and typhoid.

Preston McBride, a historian, notes that records often misreported names, ages, and family connections, illustrating how the bureaucratic systems of the time dehumanized these children. As schools like Carlisle sought to strip Native kids of their cultural identities, their hair was cut, they wore military-style uniforms, and were prohibited from speaking their native languages.

Tribal leaders reflect on these experiences as not only historical injustices but ongoing wounds that require communal and governmental healing. Amanda Cheromiah from Laguna Pueblo expressed the significance of the recent ceremonies attended by hundreds, marking a communal and personal moment of remembrance.

While some tribes express a desire to exhume their children and bring them home, the process is often complicated and costly. Policies hinder the return of remains, leading to prolonged anguish for many tribes. As the journey for repatriation continues, there’s hope that financial and moral responsibilities might lead to broader efforts to fund these crucial initiatives.

This isn't just about numbers. It's about lives lost, families torn apart, and the enduring scars of history that persist to this day, says Samuel Torres of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. He calls for entities involved to prioritize funding to aid tribes in their efforts to recover their children’s remains.