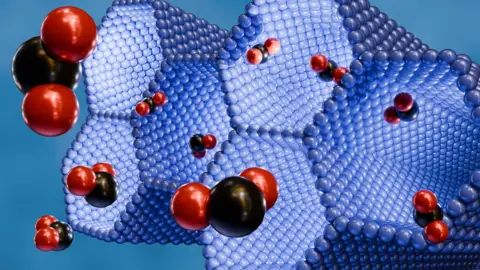

The process involved training a lone male at one breeding center in Jaisalmer to produce sperm without mating, which was then used to impregnate an adult female at a center located 200 kilometers away. This not only brings hope for the species but also opens the door to the establishment of a sperm bank that could aid future breeding efforts.

Conservationists consider this development crucial amidst the pressing threats posed by habitat loss, poaching, and flying accidents caused by power lines. The great Indian bustard is esteemed as the state bird of Rajasthan, locally referred to as "Godawan," and plays a pivotal role in controlling rodent and pest populations. Its unique physiological traits pose significant challenges as its peripheral vision assists it on land but makes it vulnerable to aerial dangers like overhead power lines.

Despite the current the rise in population due to conservation efforts—including breeding centers launched in 2018 and 2022—the conflicts between essential habitat preservation and renewable energy developments remain a substantial concern. As energy companies aggressively pursue land in Jaisalmer for solar and wind farms, they further encroach upon the bustard's dwindling territory, leading to increased human-wildlife conflicts.

The recent Supreme Court ruling that dismissed an earlier order for the underground relocation of power lines in bustard habitats has sparked debates over prioritizing energy development over avian conservation. Experts express fears that this decision could harm efforts to save the great Indian bustard, as it dismisses the critical connection between biodiversity and environmental sustainability.

This ongoing battle, poised at the intersection of wildlife conservation and renewable energy expansion, underscores the urgent necessity for comprehensive strategies aimed at protecting not only the great Indian bustard but also the ecological balance essential for human existence. Conservationists and ecologists like Sumit Dookia argue passionately that true preservation hinges on the conservation of natural habitats, emphasizing that the bird's fate is increasingly intertwined with that of the human communities around it.

Conservationists consider this development crucial amidst the pressing threats posed by habitat loss, poaching, and flying accidents caused by power lines. The great Indian bustard is esteemed as the state bird of Rajasthan, locally referred to as "Godawan," and plays a pivotal role in controlling rodent and pest populations. Its unique physiological traits pose significant challenges as its peripheral vision assists it on land but makes it vulnerable to aerial dangers like overhead power lines.

Despite the current the rise in population due to conservation efforts—including breeding centers launched in 2018 and 2022—the conflicts between essential habitat preservation and renewable energy developments remain a substantial concern. As energy companies aggressively pursue land in Jaisalmer for solar and wind farms, they further encroach upon the bustard's dwindling territory, leading to increased human-wildlife conflicts.

The recent Supreme Court ruling that dismissed an earlier order for the underground relocation of power lines in bustard habitats has sparked debates over prioritizing energy development over avian conservation. Experts express fears that this decision could harm efforts to save the great Indian bustard, as it dismisses the critical connection between biodiversity and environmental sustainability.

This ongoing battle, poised at the intersection of wildlife conservation and renewable energy expansion, underscores the urgent necessity for comprehensive strategies aimed at protecting not only the great Indian bustard but also the ecological balance essential for human existence. Conservationists and ecologists like Sumit Dookia argue passionately that true preservation hinges on the conservation of natural habitats, emphasizing that the bird's fate is increasingly intertwined with that of the human communities around it.