The white armoured police van speeds into the eastern Ukrainian town of Bilozerske, a steel cage mounted across its body to protect it from Russian drones.

They'd already lost one van, a direct hit from a drone to the front of the vehicle; the cage, and powerful rooftop drone jamming equipment, offer extra protection. But still, it's dangerous being here: the police, known as the White Angels, want to spend as little time in Bilozerske as possible.

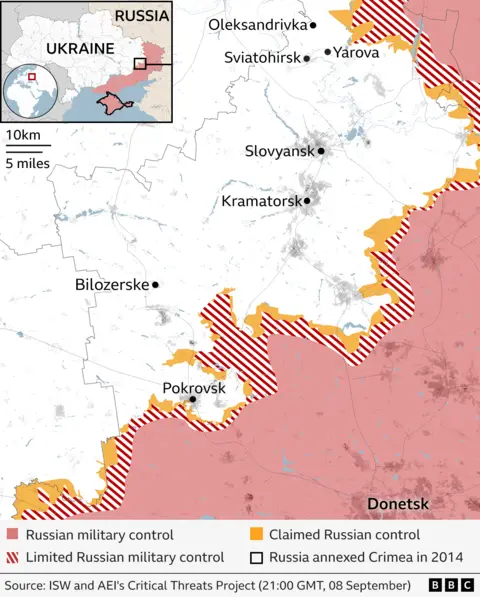

The small, pretty mining town, just nine miles (14km) from the front line, is slowly being destroyed by Russia's summer offensive. The local hospital and banks have long since closed. The stucco buildings in the town square are shattered from drone attacks, the trees along its avenues are broken and splintered. Neat rows of cottages with corrugated roofs and well-tended gardens stream past the car windows. Some are untouched, others burned-out shells.

A rough estimate is that 700 inhabitants remain in Bilozerske from a pre-war population of 16,000. But there is little evidence of them - the town already looks abandoned.

An estimated 218,000 people need evacuation from the Donetsk region, in eastern Ukraine, including 16,500 children. The area, which is crucial to the country's defence, is bearing the brunt of Russia's invasion, including daily attacks from drones and missiles. Some are unable to leave, others unwilling. Authorities will help evacuate those in front-line areas, but they can't rehouse them once they're out of danger. And despite the growing threat from Russian drones there are those who would rather take their chances than leave their homes.

The police are looking for the house of one woman who does want to leave. Their van can't make it down one of the roads. So, on foot, a policeman goes searching, the hum of the drone jammer and its invisible protection receding as he heads down a lane.

Eventually he finds the woman under the eaves of her cottage, a sign on her door reading People Live Here. She has dozens of bags and two dogs. It's too much for the police to carry: they already have evacuees and their belongings crammed inside the white van.

The woman faces a choice - leave behind her belongings, or stay. She decides to wait. There will be another evacuation team here soon and they will take her belongings too.

To stay or go is a life-or-death calculation. Civilian casualties in Ukraine reached a three-year high in July of this year, according to the latest available figures from the United Nations, with 1,674 people killed or injured. Most occur in front-line towns. The same month saw the highest number killed and injured by short-range drones since the start of the full-scale invasion, the UN said.

The nature of the threat to civilians in war has changed. Where once artillery and rocket strikes were the main threat, now they face being chased down by Russian first person view (FPV) drones, that follow and then strike.

As the police leave town, an old man pushing a bicycle appears. He's the only soul I see on the streets that day.

He's 73 years old and is risking his life for the two cooking pots he's collected on the back of his bike. His sister-in-law's house was destroyed in a Russian attack, so he came today to salvage the pots. Isn't he afraid of the drones, I ask. What will be, will be. You know, at 73 years old, I'm not afraid anymore. I've already lived my life, he says.

Life's challenges don't stop when war arrives. All Olha Zaiets wants is time to recover from her cancer surgery. Instead, the 53-year-old and her husband Oleksander Ponomarenko had to flee their home, as the Russians were too close. They are currently living in a borrowed house, but face the prospect of moving again as the front line edges closer every day.

This heart-wrenching situation continues for countless families, showcasing the resilience and dire choices they must navigate amidst uncertainty and conflict.