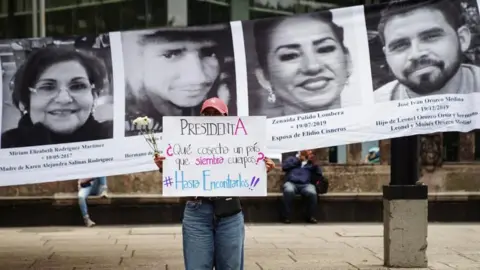

The timing of the first of several recent anti-gentrification protests in Mexico City was no coincidence - 4 July, US Independence Day.

Demonstrators gathered in Parque México in Condesa district – the epicentre of gentrification in the Mexican capital – to protest over a range of grievances.

Most were angry at exorbitant rent hikes, unregulated holiday lettings, and the endless influx of Americans and Europeans into the city's trendy neighbourhoods like Condesa, Roma, and La Juárez, forcing out long-term residents.

In Condesa, estimates suggest that one in five homes is now a short-term let or a tourist dwelling.

Others cited more prosaic changes, like restaurant menus in English, or milder hot sauces at taco stands to cater for sensitive foreign palates.

As the protest moved through gentrified streets, it turned ugly, with radical demonstrators attacking coffee shops and boutique stores aimed at tourists while chanting Fuera Gringo! meaning Gringos Out!.

President Claudia Sheinbaum condemned the violence as xenophobic, emphasizing that the demand to expel foreigners could not be accepted, regardless of the validity of gentrification grievances.

Erika Aguilar, a protester and long-term resident, shared her story of forced displacement from her family's home of over 45 years, highlighting the devastating impact of gentrification on personal lives and community unity.

Despite a recent 14-point plan by the city’s mayor meant to mitigate rising costs, many activists, including Sergio González, argue that these solutions are insufficient and only palliative. They claim deeper systemic changes are necessary to address the underlying pressures of a neoliberal economic model exacerbating the housing crisis.

The protests opened a dialogue about the influence of foreign tourism on local economies and communities, with residents divided on the implications of such shifts. As the struggle continues over rights to their neighborhoods, the impact of recent developments in Mexico City's urban landscape remains deeply felt.