Earlier this month, a Palestinian diplomat, called Husam Zomlot, was invited to a discussion at the Chatham House think tank in London.

Belgium had just joined the UK, France and other countries in promising to recognise a Palestinian state at the United Nations in New York. Dr Zomlot, Head of the Palestinian Mission to the UK, was clear that this was a significant moment.

What you will see in New York might be the actual last attempt at implementing the two-state solution, he warned.

Weeks on, that has now come to pass. The UK, Canada and Australia, who are all traditionally strong allies of Israel, have now taken this step.

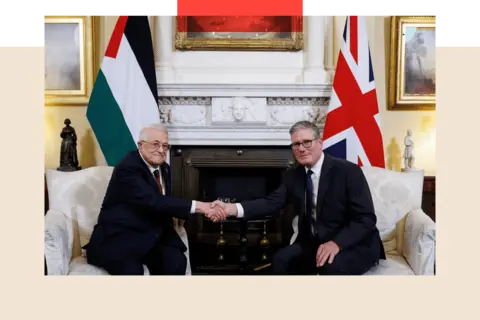

Sir Keir Starmer announced the UK's move in a video posted on social media. In it he said: In the face of the growing horror in the Middle East, we are acting to keep alive the possibility of peace and of a two-state solution.

That means a safe and secure Israel alongside a viable Palestinian state - at the moment we have neither. More than 150 countries had previously recognised a Palestinian state but the addition of the UK and the other countries is seen by many as a significant moment.

Palestine has never been more powerful worldwide than it is now, says Xavier Abu Eid, a former Palestinian official. The world is mobilised for Palestine.

But there are complicated questions to answer, including what is Palestine and is there even a state to recognise?

Four criteria for statehood are listed in the 1933 Montevideo Convention. Palestine can justifiably lay claim to two: a permanent population (although the war in Gaza has put this at enormous risk) and the capacity to enter into international relations - Dr Zomlot is proof of the latter.

But it doesn't yet fit the requirement of a defined territory. With no agreement on final borders (and no actual peace process), it's difficult to know with any certainty what is meant by Palestine.

For the Palestinians themselves, their longed-for state consists of three parts: East Jerusalem, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. All were conquered by Israel during the 1967 Six Day War.

Even a cursory glance at a map shows where the problems begin. The West Bank and Gaza Strip have been geographically separated by Israel for three quarters of a century, since Israel's independence in 1948.

In the West Bank, the presence of the Israeli military and Jewish settlers means the Palestinian Authority, established after the Oslo Accords peace deals of the 1990s, administers only around 40% of the territory. Since 1967, the expansion of settlements has eaten away at the West Bank, breaking it up into an increasingly fragmented political and economic entity.

Meanwhile, East Jerusalem, which Palestinians regard as their capital, has been ringed with Jewish settlements, gradually cutting off the city from the West Bank. Gaza's fate, of course, has been much worse. After almost two years of war, triggered by the Hamas attacks of October 2023, much of the territory has been obliterated.

Back in 1994, an agreement between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) led to the creation of the Palestinian National Authority (known simply as the Palestinian Authority or PA), which exercised partial civil control over Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank. But since a bloody conflict in 2007 between Hamas and the main PLO faction Fatah, Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank have been ruled by two rival governments: Hamas in Gaza and the internationally recognised Palestinian Authority in the West Bank, whose president is Mahmoud Abbas.

That's 77 years of geographical separation and 18 years of political division: a long time for the West Bank and Gaza Strip to drift apart. Palestinian politics has ossified in the meantime, leaving most Palestinians cynical about their leadership and pessimistic about the chances of any kind of internal reconciliation, let alone progress towards statehood.

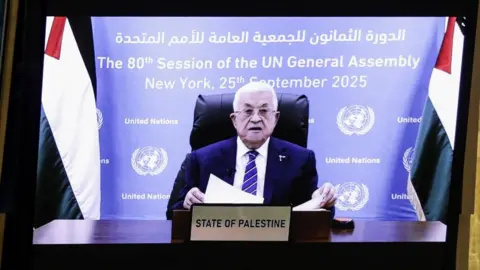

In the wake of the war which erupted in Gaza in October 2023, the issue has become even more acute. Faced with the deaths of tens of thousands of its citizens, Abbas's Palestinian Authority has been largely reduced to the role of helpless bystander.

Even before the Gaza war, Benjamin Netanyahu's opposition to Palestinian statehood was unambiguous. In February 2024, he said that, Everyone knows that I am the one who for decades blocked the establishment of a Palestinian state that would endanger our existence. Despite international calls for the Palestinian Authority to resume control over Gaza, Netanyahu insists that there will be no role for the PA in Gaza's future governance.

One thing is certain: if a Palestinian state does emerge, Hamas will not be running it. A declaration drawn up in July at the end of a three day conference sponsored by France and Saudi Arabia declared that Hamas must end its rule in Gaza and hand over its weapons to the Palestinian authority. For its part, Hamas says it's ready to hand over authority in Gaza to an independent administration of technocrats.

With Barghouti in jail, Abbas approaching 90 years of age, Hamas decimated and the West Bank in pieces, it's clear that Palestine lacks leadership and coherence. The New York Declaration committed signatories including Britain to taking tangible, timebound and irreversible steps for the peaceful settlement of the question of Palestine. But the obstacles are formidable. Israel remains implacably opposed and has threatened to retaliate through formal annexation of parts or all of the West Bank.

Whatever does emerge, it will need to answer the question of what Palestine and its leadership looks like. But for Palestinians like Diana Buttu, there's a much more pressing matter. What she would really prefer, she says, is for these countries to prevent more killing. And do something to stop it, rather than focus on the issue of statehood.