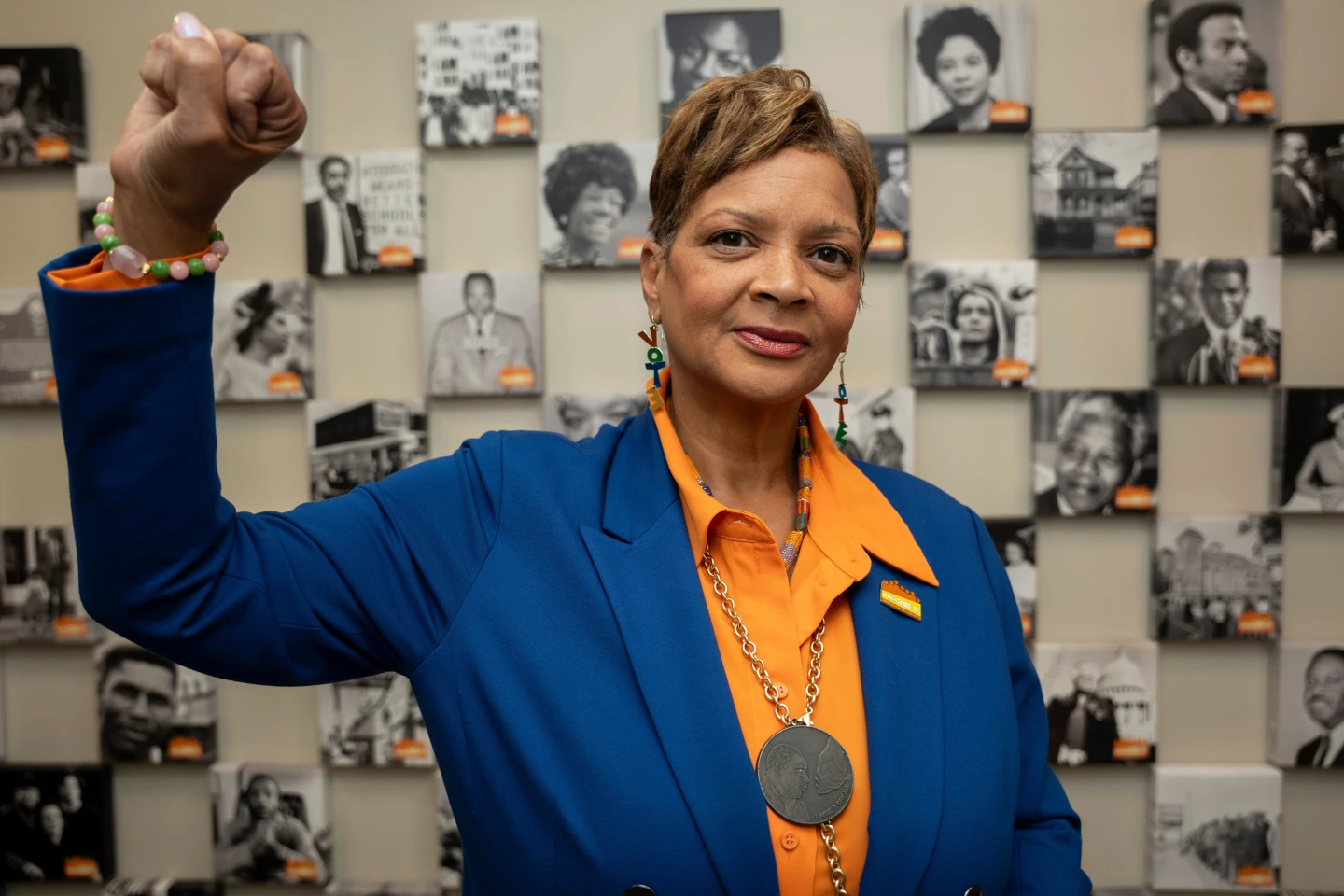

MONTGOMERY, Ala. (AP) — Doris Crenshaw was just 12 years old on December 5, 1955, when she and her sister began distributing flyers in their neighborhood, urging residents to boycott city buses in Montgomery, Alabama.

“Don’t ride the bus to work, to town, to school, or any place on Monday,” the flyers proclaimed, encouraging locals to join a mass meeting later that evening.

This urgent call to action followed the recent arrest of Rosa Parks, the secretary of the local NAACP, for refusing to relinquish her bus seat to a white passenger on segregated transport. Over the next 381 days, approximately 40,000 African American residents abstained from using the buses in a profound stand against injustice.

“This city felt a strong push to address the injustices occurring within bus systems, especially with so many arrests happening,” recalls Crenshaw, now 82.

The 70th anniversary of the Montgomery Bus Boycott is observed this Friday, with descendants of boycott organizers, including figures related to civil rights luminaries like the Reverends Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Ralph D. Abernathy, set to gather in the Alabama city. This boycott is widely recognized as the catalyst for the modern Civil Rights Movement, showcasing the strength of organized, nonviolent protest and the impact of economic boycotts — a strategy still relevant in contemporary activism.

“Any time there can be a strategic and organized response to corporate behavior or exclusionary policy, communities should be free to identify the best approach to address the harm that’s being created,” stated NAACP President Derrick Johnson.

Historically, Parks’ December 1 arrest galvanized a decision that had been in discussion among local activists. She was known, along with Crenshaw, for her leadership in the NAACP Youth Council, where young organizers would meet weekly.

Carrying out a year-long boycott required immense dedication. “We walked, and we kept walking,” Crenshaw reminisces about her daily journey to school on foot, refusing to return to the buses.

Beyond the boycott, Crenshaw has furthered her civil rights work throughout her life, leading various initiatives and mentoring youth — just as Parks had once inspired her.

Fast forward to today, and the framework of boycotting remains crucial for social change, with adaptations appropriate for the digital age. Deborah Scott, CEO of Georgia Stand-Up, emphasizes the unchanging goal of leveraging community economic power to push for social and policy reform.

13-year-old Madison Pugh resonates with the historical significance of the boycott, motivated to participate by remembering the struggles endured by those who came before her, particularly as she witnesses the efforts to dismantle diversity initiatives at companies like Target.

The message is clear: the civil rights movement’s fight for equality continues, needing both courage and collective action from the next generations.