To absolutely no one's surprise, Cameroon's Constitutional Council has proclaimed the re-election of 92-year-old President Paul Biya, the world's oldest head of state, for an eighth successive term.

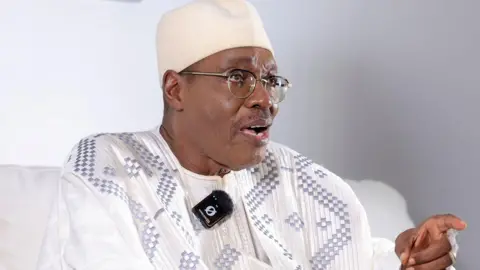

Amid rumours of a close result and claims of victory by his main challenger, former government minister Issa Tchiroma Bakary, excitement and tension had been building in the run-up to Monday's declaration.

The official outcome, victory for Biya with 53.7%, ahead of Tchiroma Bakary on 35.2%, came as both a shock and yet, for many Cameroonians, an anti-climax.

Biya's decision to stand for another seven-year mandate, after 43 years in power, was inevitably contentious, not only because of his longevity in power, but also because his style of governance has raised questions.

Extended stays abroad, habitually at the Intercontinental Hotel in Geneva or alternative more discreet locations around the Swiss lakeside city, have repeatedly triggered speculation about the extent to which he is actually governing Cameroon, or whether most decisions are in fact taken by the prime minister and ministers or the influential secretary general of the presidency, Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh.

Last year, after making a speech at a Second World War commemoration in the South of France in August and attending the China Africa summit in Beijing the next month, the president disappeared from view for almost six weeks without any announcement or explanation, sparking speculation about his health.

Even after senior officials appeared to indicate that he was, once again, in Geneva, reportedly working as usual, there was no real news until the announcement of his impending return home to the capital, Yaoundé, where he was filmed being greeted by supporters.

And this year it was not really a surprise when he squeezed a further pre-election visit to Geneva into his schedule just weeks before polling day.

Biya's inscrutable style of national leadership, rarely calling formal meetings of the full cabinet or publicly addressing complex issues, leaves a cloud of uncertainty over the goals of his administration and the formation of government policy.

At a technical level, capable ministers and officials pursue a wide range of initiatives and programmes. But the political vision and sense of direction has been largely absent.

His regime has shown itself sporadically willing to crack down on protest or detain more vocal critics. But that is not the only or perhaps even the most important factor that has kept him in power.

For it has to be said that Biya has also fulfilled a distinctive political role, acting as a balancing figure in a country marked by large social, regional and linguistic differences.

In a state whose early post-independence years were marked by debates over federalism and tensions over the form that national unity should take, he has assembled governments that include representatives of a wide range of backgrounds.

However, increasing unrest, especially in the English-speaking regions, and the lack of a clear vision for the future could signal a turning point in public tolerance of Biya's rule.

As Cameroonians tire of a system that offers them multi-party electoral expression but little hope of change, the question remains: who will succeed a leader whose grip on power grows weaker by the day?