A groundbreaking study has established that those vaccinated against shingles show a notable decrease in the likelihood of developing dementia, adding to the discourse on viral infections and cognitive health.

Shingles Vaccine Linked to Lower Dementia Risk, Study Reveals

Shingles Vaccine Linked to Lower Dementia Risk, Study Reveals

Recent research indicates that vaccination against shingles may significantly reduce dementia risk, suggesting the importance of preventative measures for brain health.

An expansive study published in the journal Nature asserts that receiving the shingles vaccine correlates with a 20 percent reduced risk of dementia for at least seven years following vaccination. This revelation underscores the importance of preventing viral infections not just for immediate physical health, but for long-term cognitive wellbeing as well.

Dr. Paul Harrison, a psychiatry professor at Oxford, who has conducted research on the shingles vaccine and dementia, commented on the findings by emphasizing that such a reduction in dementia risk is particularly significant in a public health framework, given the limited options available to slow down the onset of dementia.

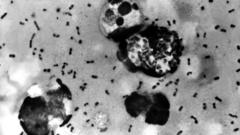

The shingles virus, originally the cause of chickenpox during childhood, can remain dormant in the nervous system for many years, only reactivating as shingles in older adults when their immune systems weaken. This reactivation can result in severe, chronic pain and discomfort, complicating overall health.

While the study points to a potential long-term benefit of shingles vaccination, further research is necessary to ascertain if these protective effects extend beyond the seven-year mark. With dementia representing a growing concern within global health, findings of this nature could inform public health strategies centered on vaccination and preventative care.

Dr. Paul Harrison, a psychiatry professor at Oxford, who has conducted research on the shingles vaccine and dementia, commented on the findings by emphasizing that such a reduction in dementia risk is particularly significant in a public health framework, given the limited options available to slow down the onset of dementia.

The shingles virus, originally the cause of chickenpox during childhood, can remain dormant in the nervous system for many years, only reactivating as shingles in older adults when their immune systems weaken. This reactivation can result in severe, chronic pain and discomfort, complicating overall health.

While the study points to a potential long-term benefit of shingles vaccination, further research is necessary to ascertain if these protective effects extend beyond the seven-year mark. With dementia representing a growing concern within global health, findings of this nature could inform public health strategies centered on vaccination and preventative care.