In the aftermath of the Syrian regime's collapse, soldiers abandon their posts and seek refuge at a reconciliation centre in Damascus, where they aim to distance themselves from past crimes and secure their civilian identities.

The Struggle for Redemption: Syrian Soldiers at a Reconciliation Centre

The Struggle for Redemption: Syrian Soldiers at a Reconciliation Centre

Following the fall of Assad, former soldiers seek safety and reintegration at a rebel-run centre in Damascus.

In the wake of the disintegration of Bashar al-Assad's regime, a "reconciliation centre" has emerged in Damascus, where defecting soldiers and militia members are seeking to shed their ties to the past. On December 6, Mohammed el-Nadaf, a soldier stationed in Homs, found himself amidst chaos as rebels from Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) advanced rapidly. Deciding he no longer wished to fight, he stripped off his uniform and headed towards his home in Tartous.

Similarly, Mohammed Ramadan, another soldier near Damascus, voiced his disillusionment with the military. "We had no orders, no information," he recalled. Many servicemen reported earning meager salaries of less than $35 per month, forcing them to take on additional jobs just to survive in a country experiencing severe economic distress.

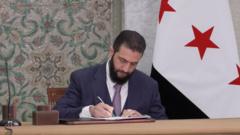

Two weeks post-regime collapse, both soldiers appeared at a reconciliation centre in Damascus. This venue, a former Baath Party office, serves as a sanctuary for military personnel, police officers, and intelligence agents eager to exchange their weapons for civilian identity cards, thereby facilitating their reintegration into society. The HTS has declared a general amnesty for those formerly aligned with Assad's regime.

Waleed Abdrabuh, overseeing the Damascus reconciliation centre, articulated their mission to retrieve former regime-issued weapons and to help soldiers transition back to civilian life. The need for civilian documentation is crucial, given that former conscripts had their IDs confiscated when they enlisted, complicating their reentry into society.

As they waited in line with hundreds of others, many defectors expressed a strong desire to dissociate from the Assad regime. Mohammed al-Nadaf openly condemned the regime's atrocities, insisting, "I did everything to avoid being a part of massacres." Somar al-Hamwi, a veteran of 24 years, reflected on the ignorance surrounding the regime's brutal actions, which he claims he did not witness.

While the atmosphere at the centre seemed amicable amidst the ruins of civil conflict, there looms a tension. Reports of violent reprisals and revenge killings are surfacing, with concerns for safety growing among the population. The recent deaths of three judges in Masyaf, alleged to be targeted for their Alawite affiliation, underscores the fragile tensions between different factions.

The family of Mounzer Hassan, one of the slain judges, are vocal in their distress. His widow, Nadine Abdullah, expressed the belief that his murder was rooted in sectarianism rather than his role within the regime. This sentiment highlights the difficult path ahead, as HTS vows to address such violence while attempting to uphold their amnesty commitments.

As Syria wades through a complex and delicate turning point, the reconciliation centre stands as both a refuge for former soldiers seeking redemption and an emblem of the challenges facing the nation’s potential rebuilding.

Similarly, Mohammed Ramadan, another soldier near Damascus, voiced his disillusionment with the military. "We had no orders, no information," he recalled. Many servicemen reported earning meager salaries of less than $35 per month, forcing them to take on additional jobs just to survive in a country experiencing severe economic distress.

Two weeks post-regime collapse, both soldiers appeared at a reconciliation centre in Damascus. This venue, a former Baath Party office, serves as a sanctuary for military personnel, police officers, and intelligence agents eager to exchange their weapons for civilian identity cards, thereby facilitating their reintegration into society. The HTS has declared a general amnesty for those formerly aligned with Assad's regime.

Waleed Abdrabuh, overseeing the Damascus reconciliation centre, articulated their mission to retrieve former regime-issued weapons and to help soldiers transition back to civilian life. The need for civilian documentation is crucial, given that former conscripts had their IDs confiscated when they enlisted, complicating their reentry into society.

As they waited in line with hundreds of others, many defectors expressed a strong desire to dissociate from the Assad regime. Mohammed al-Nadaf openly condemned the regime's atrocities, insisting, "I did everything to avoid being a part of massacres." Somar al-Hamwi, a veteran of 24 years, reflected on the ignorance surrounding the regime's brutal actions, which he claims he did not witness.

While the atmosphere at the centre seemed amicable amidst the ruins of civil conflict, there looms a tension. Reports of violent reprisals and revenge killings are surfacing, with concerns for safety growing among the population. The recent deaths of three judges in Masyaf, alleged to be targeted for their Alawite affiliation, underscores the fragile tensions between different factions.

The family of Mounzer Hassan, one of the slain judges, are vocal in their distress. His widow, Nadine Abdullah, expressed the belief that his murder was rooted in sectarianism rather than his role within the regime. This sentiment highlights the difficult path ahead, as HTS vows to address such violence while attempting to uphold their amnesty commitments.

As Syria wades through a complex and delicate turning point, the reconciliation centre stands as both a refuge for former soldiers seeking redemption and an emblem of the challenges facing the nation’s potential rebuilding.