Chile is perceived by many of its neighbours in the Latin American region as a safer, more stable haven.

But inside the country, that perception has unravelled as voters worried about security, immigration and crime chose José Antonio Kast to be their next president.

Kast is a hardline conservative who has praised General Augusto Pinochet, Chile's former right-wing dictator whose US-backed coup ushered in 17 years of military rule marked by torture, disappearances and censorship.

To his critics, Kast's family history, including his German-born father's membership in the Nazi Party and his brother's time as a minister under Pinochet, is unsettling.

However, some of Kast's supporters openly defend Pinochet's rule, arguing that Chile was more peaceful then.

In a nod to Chile's past and to accusations levelled at other right-wing leaders in the region after they imposed military crackdowns on organised crime, the 59-year-old pledged in his first speech as president-elect that his promise to lead an emergency government would not mean authoritarianism.

Sunday's election makes Chile the latest country in Latin America to decisively swing from the left to the right, following Argentina, Bolivia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador and Panama.

Kast's victory places Chile within a growing bloc of conservative governments likely to align with US President Donald Trump, particularly on migration and security.

In some cases, like that of Argentina, inflation and economic crisis drove the shift. In others, it was a backlash against leftist governments mired in corruption or infighting.

In Chile, immigration and crime seemed to swing it.

Kast promised a border wall and mass deportations of undocumented migrants.

At rallies, he counted down the days until the inauguration and warned that those without papers should leave by then if they wanted the chance to ever return.

His message resonated in a country which has seen a rapid growth in its foreign-born population. Government figures show that by 2023 there were nearly two million non-nationals living in Chile, a 46% increase from 2018.

The government estimates about 336,000 undocumented migrants live in Chile, many from Venezuela.

The speed of that change has unsettled many Chileans.

Chile was not prepared to receive the wave of immigration it did, says Jeremías Alonso, a Kast supporter who volunteered to mobilise young voters during the campaign.

He rejects critics' accusations that Kast's rhetoric amounts to xenophobia.

What Kast is saying is that foreigners should come to Chile, let them come to work, but they should enter properly through the door, not through the window, he says, arguing that undocumented migrants are a strain on taxpayer-funded public services.

He says his working-class neighbourhood has experienced the social changes that irregular immigration brings in terms of crime, drug addiction and security.

Kast has blamed rising crime on immigration, an allegation that resonates politically even as the number of murders has fallen since peaking in 2022, and despite some studies suggesting migrants commit fewer crimes on average.

Many voters cite organised crime, drug trafficking, thefts and carjackings as contributing towards their sense of insecurity.

Kast's victory message is that migrants will be welcome if they comply with the law, criminals will be locked up and order will return to the streets.

He, like Trump, is expected to move quickly to demonstrate an iron fist approach, deploying the military to the border and probably promoting his crackdown through social media.

But in practice, large-scale deportations will be difficult.

Venezuela does not accept deportees from Chile and deportations have so far been limited.

Kast seems to hope his rhetoric will encourage irregular migrants to leave voluntarily. But this is unlikely to compel hundreds of thousands to pack up.

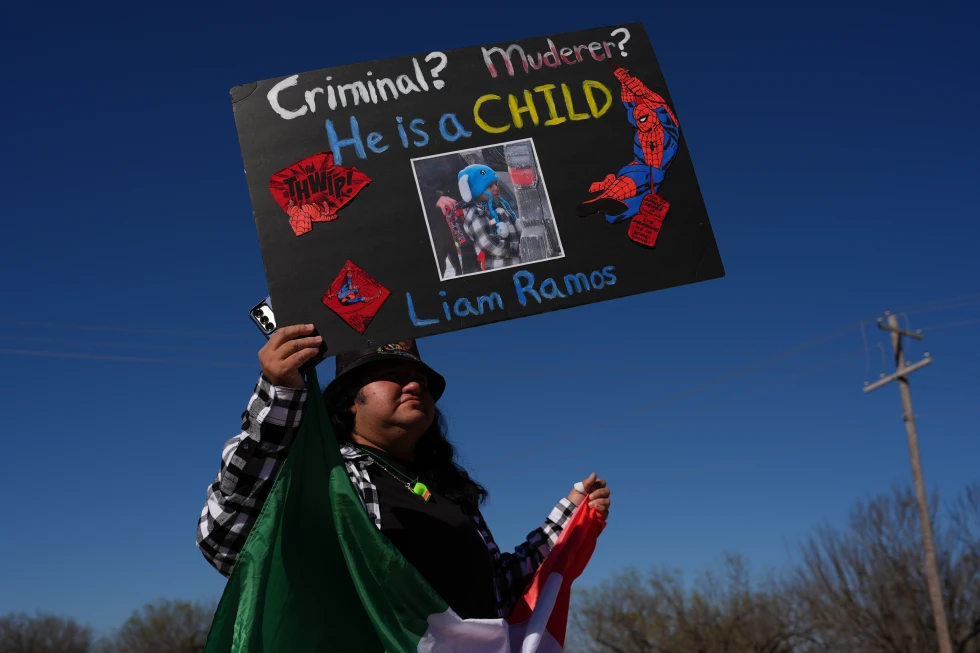

For irregular migrants already in Chile, the future feels uncertain.

Gabriel Funez, a Venezuelan waiter, moved to Chile four years ago, crossing the land border irregularly to escape his country's very, very bad economic situation.

He has since submitted his documents to police and immigration authorities and received a temporary ID so he can pay taxes but has so far had no response to his visa request.

His salary is currently being paid into a friend's bank account. I'm basically a ghost here, he says.

While he fears deportation, his bigger concern is a rise in xenophobia, which he says has already increased.

Kast is expressing what many Chileans want to express. He's validating it, he said.

He recalls how at the restaurant where he works, he served diners who were discussing how migrants should leave.

It was uncomfortable. I'm a foreigner, and I'm hearing all those super hurtful words.

He explains that about 90% percent of the restaurant's staff are migrants.

With migrants increasingly key to Chilean businesses, Kast could come up against opposition from those relying on foreign labour for their business.

Carlos Alberto Cossio, a Bolivian national who has lived in Chile for 35 years, runs a business making and delivering salteñas, savoury Bolivian pastries.

He says he has often employed workers from Haiti, Colombia and Venezuela and insists that the migrant workforce is very important.

He explains that migrants are eager to work and less likely to change jobs as they rely on their employer for a contract visa until they are issued with a permanent visa.

Many companies, especially in fruit harvesting, employ migrant workers who are not necessarily registered, he adds.

Expelling unregistered workers will impact Chile's export economy and make raw materials more expensive, he warns.

Mr Cossio acknowledges that there has been some friction since large numbers of migrants arrived from Venezuela to escape the economic and political crisis there.

Many of the customs they have brought haven't been compatible with Chilean customs, he says, lamenting how this has damaged the reputation of migrants who want to work and contribute.

Mr Kast's party lacks a majority in Congress, meaning some of his proposals, from tougher sentencing to maximum-security prisons, may require compromise and negotiation.

But for many voters, the perception of control may matter just as much as delivering results as anxiety over crime, insecurity and migration is sweeping the continent.