When Prabowo Subianto campaigned to become Indonesia's new president, he promised dynamic economic growth and major social change.

But his first year in office has not lived up to this populist platform. Rather, his ambitious pledges have been confronted by the realities of South East Asia's biggest economy.

A frustrated youth, worried about jobs, took to the streets in late August to protest against the rising cost of living, corruption and inequality - the government was forced to roll back the perks for politicians that had triggered public fury. There had been huge protests earlier in the year too, against budget cuts that hit healthcare and education spending.

What didn't help was that this coincided with an expensive free school meals programme - at an annual cost of $28bn (£20.8bn). A centrepiece of Prabowo's agenda, it aims to tackle child malnutrition, improve education outcomes and stimulate the economy. Officials describe it as an investment in Indonesia's future.

Except, in recent months images have emerged showing weak, dehydrated children - some as young as seven - hooked up to intravenous drips. They were suffering from food poisoning after eating the free lunches.

With more than 9,000 children falling ill since the scheme was rolled out in January, critics are questioning whether it's delivering at all, or straining public resources while racking up debt.

Analysts warn all of these challenges highlight broader issues in public spending and oversight - and those, in turn, point to deeper strains in Indonesia's $1.4tn economy.

It is a critical time for the vast archipelago of more than 280 million people, spread across thousands of islands.

Despite steady annual growth of roughly 5% in recent years, Indonesia is feeling the pressure of slowing global demand, rising living costs and competition from regional neighbours like Vietnam and Malaysia. Both of those countries have successfully attracted foreign companies trying to diversify production away from China.

The protests in August, which left 10 people dead, captured the extent of public anger over Prabowo's government. Demonstrators accused it of prioritising prestige policies and projects over providing economic support.

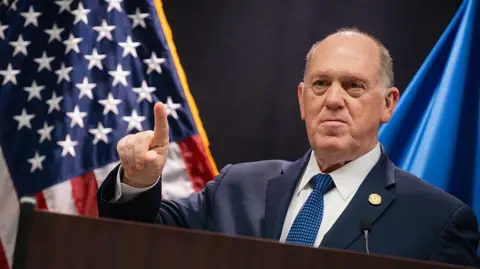

Prabowo - who has set an ambitious growth target of 8% by 2029 - and his ministers continue to defend their policies, saying they will create jobs and stimulate demand.

Indonesia's Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs Airlangga Hartarto noted that higher growth is achievable with proper management.

But the ambitious commitments like the free school meals program have led some to question Prabowo's priorities. Critics are urging a halt to the scheme, citing its ineffectiveness and safety issues.

Challenges remain monumental as the president navigates economic slowdowns, rising public dissatisfaction, and the search for sustainable foreign investment.