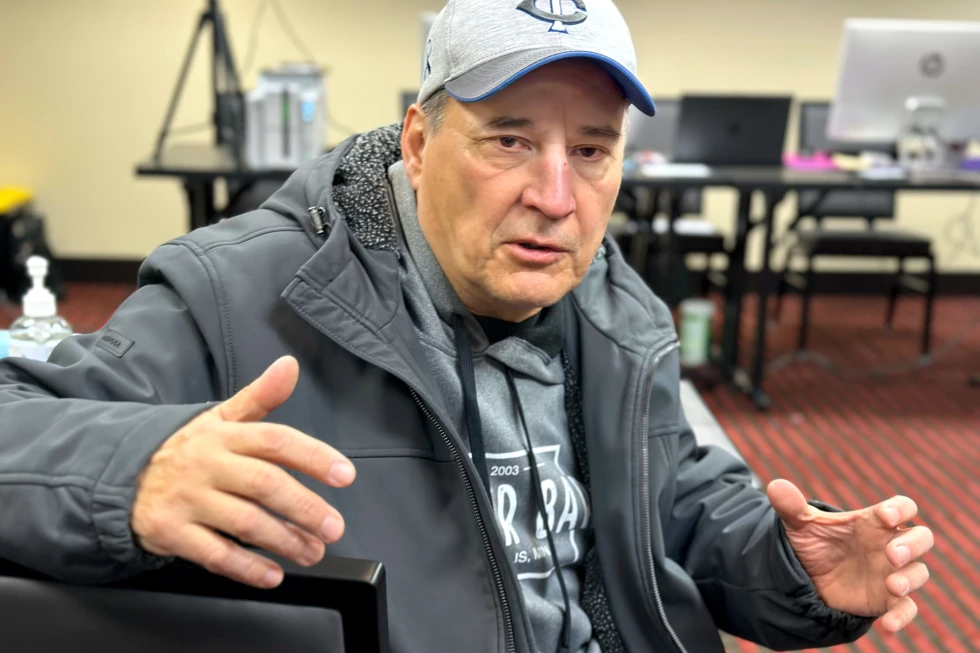

MINNEAPOLIS (AP) — As U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) ramps up its presence in Minneapolis, Shane Mantz dug his Choctaw Nation citizenship card out of his dresser and slipped it into his wallet. With strangers often mistaking him for Latino, the pest-control company manager harbors fears of potential ICE raids.

Mantz's concerns are shared among many Native Americans, prompting a movement to carry tribal documents as proof of U.S. citizenship. In response, several of the 575 federally recognized Native nations are reducing barriers to obtaining tribal IDs by waiving fees and expediting the application process.

This effort marks the first widespread use of tribal IDs as a means of asserting citizenship and protecting individuals from federal law enforcement actions. David Wilkins from the University of Richmond remarked, “I don’t think there’s anything historically comparable.”

With the U.S. Department of Homeland Security unresponsive to multiple inquiries, the situation grows tense as many Native Americans secure documentation that proves their rights on their own land. Jaqueline De León, a senior attorney with the Native American Rights Fund, expressed the injustice, saying, “As the first people of this land, there’s no reason why Native Americans should have their citizenship questioned.”

Native Identity in a New Age of Fear

Since the mid-1800s, the U.S. government has systematically recorded genealogies of Native Americans to determine eligibility for various federally mandated services. Starting in the late 1960s, tribal nations began issuing identification, enabling the use of tribal IDs for voting, employment, and air travel.

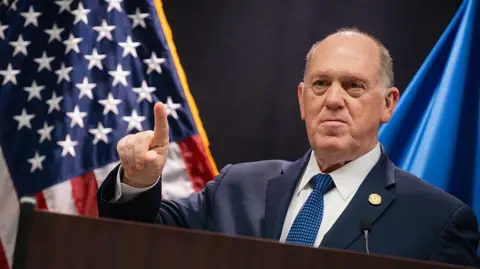

In urban areas, where around 70% of Native Americans reside, including the large population in the Twin Cities, the need for identification has become critical. Recently, a top ICE official announced the largest immigration operation to date, a move that has led to thousands of arrests.

In Minneapolis, representatives from numerous tribal nations traveled hundreds of miles to facilitate ID applications for local members. Turtle Mountain citizen Faron Houle emphasized raising awareness of the need for tribal IDs due to racial profiling, asserting, “You just get nervous.”

Events held to aid urban tribal citizens showcased a community resource-sharing spirit as several leaders made the journey to support those unable to travel to their reservations.

Claims of ICE Harassment

Alarming reports have emerged from across tribal nations. Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren reported that citizens in Arizona and New Mexico face harassment from ICE officers. Several high-profile incidents include actress Elaine Miles, who experienced questioning from ICE about her tribal ID in Washington state. The Oglala Sioux Tribe recently announced a ban on ICE presence within their reservation.

Peter Yazzie, a Navajo construction worker, recounted his experience being wrongfully detained after ICE officers targeted him at a gas station. He lamented the dehumanizing nature of the encounter, which is symptomatic of a broader issue faced by Indigenous peoples today.

Mantz, navigating neighborhoods active with ICE operations, articulates the disruptive emotional weight of needing to prove one’s identity. “Why do we have to carry these documents? Who are you to ask us to prove who we are?” he pondered.