For years, scientists have warned that bird flu - better known as H5N1 - could one day make the dangerous leap from birds to humans and trigger a global health crisis.

Avian flu - a type of influenza - is entrenched across South and South-East Asia and has occasionally infected humans since emerging in China in the late 1990s. From 2003 to August 2025, the World Health Organization (WHO) has reported 990 human H5N1 cases across 25 countries, including 475 deaths - a 48% fatality rate.

In the US alone, the virus has struck more than 180 million birds, spread to over 1,000 dairy herds in 18 states, and infected at least 70 people - mostly farmworkers - causing several hospitalisations and one death. In January, three tigers and a leopard died at a wildlife rescue centre in India's Nagpur city from the virus that typically infects birds.

Symptoms in humans mimic a severe flu: high fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches and, at times, conjunctivitis. Some people have no symptoms at all. The risk to humans remains low, but authorities are watching H5N1 closely for any shift that could make it spread more easily.

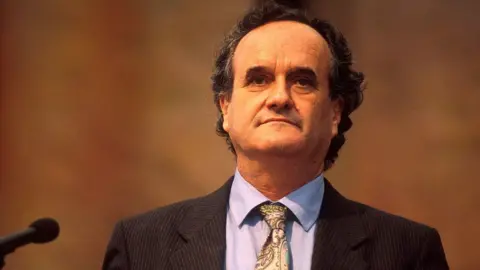

That concern prompted new peer-reviewed modelling by Indian researchers Philip Cherian and Gautam Menon of Ashoka University, which simulates how an H5N1 outbreak might unfold in humans and what early interventions could stop it before it spreads.

In other words, the model published in the BMC Public Health journal uses real-world data and computer simulations to illustrate how an outbreak might expand in reality.

The threat of an H5N1 pandemic in humans is a genuine one, but we can hope to forestall it through better surveillance and a more nimble public-health response, Prof Menon stated.

A bird flu pandemic, researchers say, would begin quietly: a single infected bird passing the virus to a human – most likely a farmer, market worker, or someone handling poultry. From there, the danger lies not in that first infection but in what follows: sustainable human-to-human transmission.

Using an open-source simulation platform originally built for Covid-19 modelling, the study tracked how the outbreak might develop.

The paper emphasizes that policymakers need to act swiftly; once cases exceed two to ten, the disease could spread beyond primary and secondary contacts. Effective interventions, such as culling birds and quarantining close contacts, can prevent further transmission if implemented promptly.

Quarantine orders introduced too early could keep families together for long periods, raising chances of transmission within households. Conversely, delayed quarantine measures have been shown to be largely ineffective.

In conclusion, while the models provide crucial insights for prevention strategies against H5N1, researchers acknowledge the complexity of disease transmission, highlighting the need for adaptive responses as the public health landscape changes.