A year ago, the war that President Bashar al-Assad seemed to have won was turned upside down.

A rebel force had broken out of Idlib, a Syrian province on the border with Turkey, and was storming towards Damascus. It was led by a man known as Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, and his militia group, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). Jolani was a nom-de-guerre, reflecting his family's roots in the Golan Heights, Syria's southern highlands, annexed by Israel after it was occupied in 1967. His real name is Ahmed al-Sharaa.

One year later, he is interim president, and Bashar al-Assad is in a gilded exile in Russia.

Syria is still in ruins. In every city and village I have visited this last 10 days, people were living in skeletal buildings gutted by war. But for all the new Syria's problems, it feels much lighter without the crushing, cruel weight of the Assads.

Sharaa has found the going easier abroad than at home. He has won the argument with Saudi Arabia and the West that he is Syria's best chance of a stable future. In May, the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia arranged a brief meeting between al-Sharaa and US President Donald Trump. Afterwards, Trump called him a young attractive tough guy.

At home, Syrians know his weaknesses and the problems Syria faces better than foreigners. Sharaa's writ does not run in the north-east, where the Kurds are in control, or parts of the south where Syrian Druze, another minority sect, want a separate state backed by their Israeli allies.

On the coast Alawites – Assad's sect – fear a repeat of the massacres they suffered in March.

A year ago, the new masters of Damascus, like most of the armed rebels in Syria, were Sunni Islamists. Sharaa, their leader, had a long history fighting for al-Qaeda in Iraq, where he had been imprisoned by the Americans, and then was a senior commander with the group that became Islamic State. Later, as he built his power base in Syria, he broke with and fought both IS and al-Qaeda.

People who had travelled to Idlib to see him said that he had developed a much more pragmatic set of beliefs, better suited to governing Syria, with its spectrum of religious sects. Sunnis are the majority. As well as Kurds and Druze, there are Christians, many of whom find it hard to forget Sharaa's jihadist past.

Sharaa took power amid huge uncertainty about what he might do, and what might be done to him by his enemies. Among them were dark fears that the jihadist extremists of Islamic State, still existing in sleeper cells, could try to kill him, or cause chaos with mass casualty attacks in Damascus.

Jihadists rage on social media about Sharaa's charm offensive in the west. After he agreed to join the US-led coalition against Islamic State, prominent voices online branded him an apostate, a Muslim who had turned on his own religion. Extremists could take that as a licence to kill.

The reality is that IS in Syria is weak. Its attacks this year have been mostly against Kurdish-led forces in the north-east.

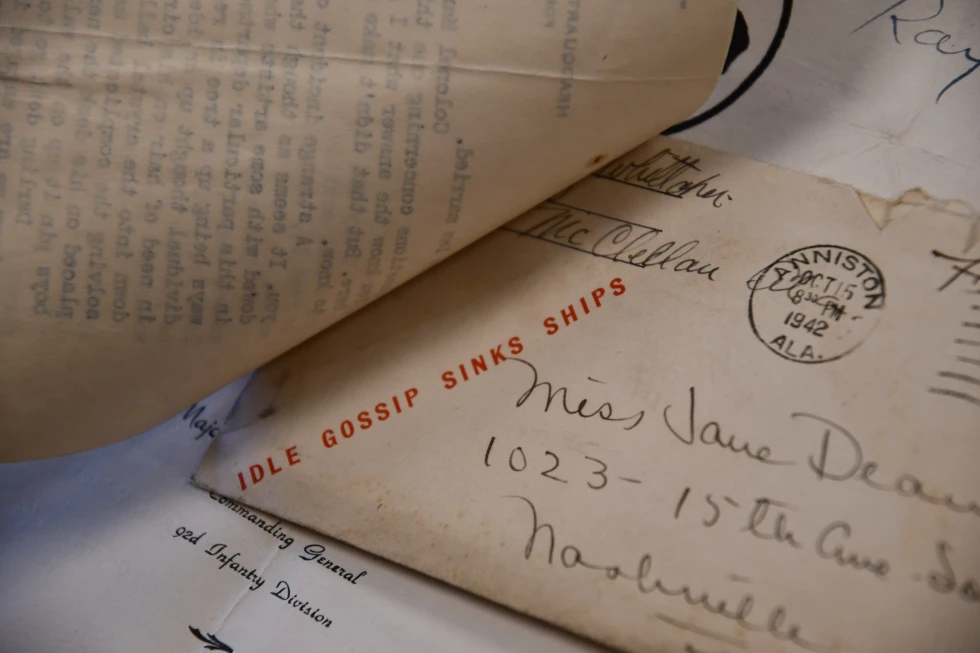

Sharaa's overtures to the west have been remarkably successful. Within two weeks of taking power in Syria, he received a delegation of senior American diplomats. Immediately, the Americans scrapped the $10 million bounty that they had placed on his arrest. Since then, sanctions imposed on Assad's Syria have been steadily reduced. The most swingeing, the Caesar Act, has been suspended and could be repealed by the US Congress in the new year.

Trump's welcome in the Oval Office was relaxed. He sprayed Sharaa with Trump-branded cologne, before presenting him with his own supply to take home for his wife, jokingly asking him how many he has. One, Sharaa answered, as he blinked away clouds of fragrance.

The future is difficult for Syrians. With no rebuilding fund and ongoing sectarian tension unresolved, many live in fear. We go to sleep and wake up afraid, says Umm Mohammad, expressing the sentiments of countless families struggling to navigate this uncertain new era.